[Note: this is the 4th and final part of a series. If you have not yet read them, you may want to first read Part 1: The Launch, Part 2: The International Consultation, and Part 3: Moving To Implementation]

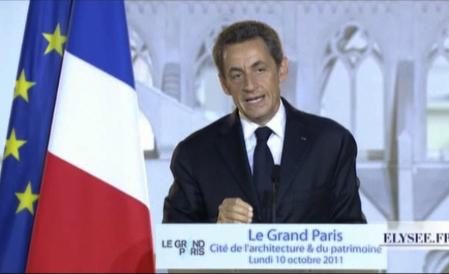

On October 10, 2011, President Nicolas Sarkozy was back at the Cité de l’Architecture for what had by now become a tradition of a biennial visit. He summarized where Le Grand Paris stood:

– Agreement and funding for a transportation master plan that includes €20 billion for the new high-speed urban transit network and €12.5 for improvements and extensions to existing lines;

– Urban planning for ten development poles, including the Saclay area south-west of Paris that the government wants to turn into a global center of science, technology and entrepreneurship;

– A continued ambition to build 70,000 new homes a year in the Paris region, despite the acknowledged fact that the actual number of new homes built had stayed stubbornly stable at around 40,000 since this goal was first announced;

– A number of grands projets aimed at maintaining Paris’s position as a capital of culture (Palais de Tokyo, Maison de l’Histoire, Philharmonie de Paris, etc).

President Sarkozy concluded his speech by affirming his will that “things are completed to the end, without any possible return backward” and asserting that “I still have for le Grand Paris the same enthusiasm I had four years ago, maybe even a bit more”.

So where does all this leave Le Grand Paris, after four years of effort?

The consensus seems to be that the Grand Paris Express transit system, with its financing agreed, is firmly on the rails and will happen. So the question is: will Le Grand Paris boil down to a new public transportation system or will there actually be an integrated, holistic, ambitious vision for the Paris region? Will something of the spirit of the “new global program for greater Paris” that President Sarkozy called for remain?

At the present juncture, the cold reality is that this seems unlikely. A dynamic was launched by the international consultation, but efforts to make it reality on the ground are divided among many different stakeholders and processes.

– The work of the ten teams of the international consultation was supposed to continue through the Atelier International du Grand Paris (AIGP), which has taken an approach of promoting 650 projects across the region. But the architects involved are complaining that they have no resources to work with and it is unclear what role the AIGP can play. Even the President of the AIGP, Pierre Mansat, seems to have little hope, saying that ” the hopes that local governments had placed in Le Grand Paris are at risk of being disappointed, as they often are, by empty words” [JDD, 9 October 2011].

– A number of territories are, or are likely to become, subject to Territorial Development Contracts (CDT) or Operations of National Interest (OIN) – two very different mechanisms that have the common characteristic of maintaining an important role for the national government in the urban planning measures (defining development zones, expropriating, approving construction permits).

– The development of a regional plan has been relaunched in order to incorporate the transportation network announced in the law of July 2010, but it is unclear if any other aspect will be reworked to incorporate the output of the international consultation – in fact it seems impossible to substantially change the plan if it is to be fully approved and operational by the end of 2013. Most importantly, it is unlikely that the new plan will address the extent of the urbanized footprint of the Paris region, an issue of the utmost importance to the teams of the consultation.

– In addition to all this, the local governments are continuing the work they have been doing all along. The City of Paris is implementing a number of major projects, some developed jointly with towns on its periphery. The various development poles around Paris have created their own development authorities. Overall, there is a plethora of stakeholders leading all sorts of projects.

As Bertrand Lemoine, Director the AIGP, summarized: “It is all about making this constellation of projects, converge toward a common destiny, a common identity.”

Has the Le Grand Paris initiative actually been helpful?

The original premise of Le Grand Paris was seductive. Instead of another museum, library or opera house, Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidential legacy would be the redefinition of the whole Paris metropolis. This type of broad, visionary thinking was what animated Napoléon III’s transformation of the city in the 1850s and 1860s, creating the city largely as we know it, and it is clearly the approach needed to address the scale of challenges the metropolitan region is facing. The international consultation was a great success, generating novel and audacious thinking that shifted the terms of the entire discussion. Most interestingly, Le Grand Paris has made the future of Paris a subject of broad public debate to an extent no one thought possible.

At the same time, President Sarkozy’s approach had serious flaws. The most damning was that it wrought havoc on the proper sequence of events in a planning process. The strategic, idea-generation phase happened late in the process, after the official regional plan was developed and after the Ministry had reached its own conclusions about what to do – obviously a non-optimal state of affairs. The first major decision made was about the transportation network, despite the fact that, as Roland Castro stated, “none of the teams [of the consultation] would have started with the transportation network.” [Speaking in “La Grande Table”, France Culture, October 21, 2011] The desire to do everything at the same time ended up in insufficiently thought-through decisions and a great deal of confusion among stakeholders.

Nicolas Sarkozy was certainly correct when he said that “we clearly see that our organization in municipalities, départements, and region was absolutely incapable of driving forward a project of this nature”. Still, the approach of the national government, rather than bringing together the various local governments, alienated them and created divisions.

Christian Blanc was a large part of this problem. He may have seen himself as a present-day Georges-Eugène Haussmann, barreling through opposition to achieve concrete results, but he lacked Haussmann’s political adeptness. He not only alienated important stakeholders through his arrogance and inflexibility, but he also, as Jean Nouvel demonstrated in his editorial in Le Monde of 19 May, 2010, showed a weak grasp of the basics of urban transformation.

President Sarkozy has been adamant that “it is extremely important that architecture and urbanism remain at the heart of the project.” He admitted that “this is not the will of the administrations, as I have known since the beginning, but is the key to our approach.” At this point, even with the existence of the AIGP, it is very unclear how his objective of keeping a holistic approach to the city at the center of Le Grand Paris will be achieved.

There is a core political issue with the whole enterprise in the idea that the President of France could claim the planning of Paris as his own political victory, when both the President of the Île-de-France region and the Mayor of Paris are leading members of the Socialist opposition. It is inevitable that Bertrand Delanoë, the Mayor of Paris, feels that the President’s actions “amount to little accomplished and a great deal of time lost.” [see press release] Both Delanoë and the President of the Île-de-France region, Jean-Paul Huchon, were irritated at President Sarkozy’s appropriation, in his 2011 speech, of projects started by the local governments before Sarkozy was even elected as accomplishments of Le Grand Paris.

France will hold presidential elections in May 2012. If Nicolas Sarkozy is reelected, it will be interesting to see how he gives Le Grand Paris a new impetus. If the other major candidate, the Socialist François Hollande, is elected, he is likely to continue the undertaking but seek to reposition it. The critical question will be the future role he gives the national government, and the possibility of a shift to a governance model where the local governments will have a leading role.

France will hold presidential elections in May 2012. If Nicolas Sarkozy is reelected, it will be interesting to see how he gives Le Grand Paris a new impetus. If the other major candidate, the Socialist François Hollande, is elected, he is likely to continue the undertaking but seek to reposition it. The critical question will be the future role he gives the national government, and the possibility of a shift to a governance model where the local governments will have a leading role.

The risk, as historian and Grand Paris consultant Pascal Ory has indicated, is that the political determination will stop at the transportation network, and that the de facto result of Le Grand Paris will therefore be a piece of infrastructure without any coherent overall urban planning. The fact that President Sarkozy has started pointing to a constellation of high-profile architecture projects, like the Philharmonie de Paris and the Villa Medici in Montfermeil as parts of Le Grand Paris, indicates a troubling drift away from the planning ideals of the original vision.

Le Grand Paris has generated unprecedented hope and ambition for a genuine vision for the future of the metropolis. We are now at the point where we will see if the reality lives up to the expectations.

Selected Bibliography

Philippe Panerai, Paris métropole, formes et échelles du grand Paris, Éditions de la Villette, 2008

Christian Blanc, Le Grand Paris du XXIème siècle, Le Cherche-Midi, 2010

Marc Wiel, Le Grand Paris, premier conflit né de la décentralisation, L’Harmattan, 2010

Marion Bertone, Michel Leloup, Les coulisses de la consultation, Archibooks, 2009

Special issues of various magazines: AMC, Urbanisme, L’architecture d’aujourd’hui

Report by Senator Philippe Dallier presented on April 8th, 2008

Links (in French)

Le Grand Paris (Ministry of Urban Affairs Site)

Le Grand Paris (Ministry of Culture site)

Atelier International du Grand Paris

Institut d’Aménagement et d’Urbanisme – Île-de-France (regional government urban planning office)

Agence Parisienne d’Urbanisme (City of Paris-led urban planning office)

Paris Métropole (forum bringing together local governments of the Paris region)

Related posts:

Le Grand Paris – Part 1: The Launch

6 thoughts on “Le Grand Paris – Part 4: Where Things Stand”